The picture of the coronavirus outbreak now coming into focus is one of mostly mild cases, with increased risk of severe symptoms and death for the elderly and patients with pre-existing conditions, a new Chinese study suggests.

The research from the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention is based on more than 72,000 patient records of COVID-19 reported nationwide through Feb. 11.

Among the more than 44,000 confirmed cases with symptoms, nearly 87 per cent of patients were aged 30 to 79, with nearly three-quarters diagnosed in China's Hubei province.

About four out of five cases were considered mild, and didn't lead to pneumonia, the researchers said.

Another 14 per cent were classified as severe, causing symptoms such as pneumonia and shortness of breath.

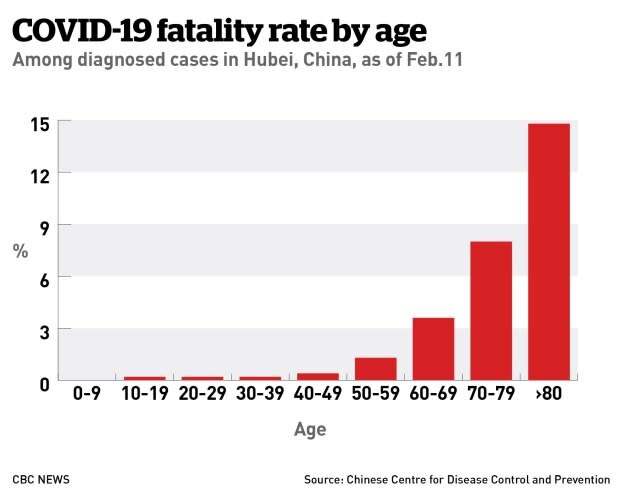

And about five per cent of patients developed critical disease, such as respiratory failure, septic shock and multi-organ failure. Among the 1,023 deaths, most were among those aged 60 and older, and many had other medical conditions such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

The case fatality rate was 2.3 per cent, the study says.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the World Health Organization, says the data offers a better understanding of the range of people affected, and the severity of the disease and its mortality rate, which will be important in helping his organization to provide solid evidence-based advice to countries.

"The data also appear to show a decline in new cases. This trend must be interpreted very cautiously," he told reporters. "Trends can change as new populations are affected."

The outbreak spread rapidly from Wuhan to the rest of China within about a month, the researchers said. And it did so despite a massive public health response that included the shutdown of entire cities, the cancellation of Chinese New Year celebrations, and the promotion of hand-washing, wearing medical masks and seeking immediate medical attention.

"In light of this rapid spread, it is fortunate that COVID-19 has been mild for 81 per cent of patients," the authors wrote.

The researchers said the fatality rate for males was 2.8 per cent and 1.7 per cent for females.

In previous, smaller studies of the outbreak in China, the fatality rates among confirmed cases were also about two per cent, said Dr. Susy Hota, medical director of infection prevention and control at Toronto's University Health Network.

Hota called the Chinese study an important piece of information. But the overall fatality rate remains unclear, she said, because of the pool of mild cases that don't get diagnosed and counted.

Death-time delays

By comparison, in 2003, the case fatality rate for SARS, caused by another coronavirus, was estimated at 10 per cent.

"One thing that surprised me was the presentation of simple case fatality ratios without adjusting or accounting for the time delays from onset to death," Benjamin Cowling, of the School of Public Health at the University of Hong Kong, said in an email.

He studies respiratory virus transmission and was not involved in the Chinese study.

Since the average time from when illness occurs to death is around three to four weeks, Cowling said, it would be reasonable to predict that more of the 12,000 people who became ill after Feb. 1 will ultimately succumb to the infection.

The researchers say a major contribution of the study is its description of the epidemic curve of COVID-19 — a visual display charting when people started falling ill. The data appears to indicate a common source in December, which is consistent with the hypothesis that the virus was transmitted from a still-unknown animal to humans at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan.

The virus then seemed to adapt to transmit more efficiently between humans.

Hota said cases exported from China show relatively limited person-to-person transmission, usually within households or among close contacts.

"I think what we're seeing, pretty consistently, is that it does transmit from person to person, but it's not something that's spreading like wildfire," said Hota, an infectious disease physician.

The researchers' epidemic curve suggests the outbreak peaked around Jan. 23 to 26.

Major strain on health services

More than 1,700 health-care workers in China have been infected, including five who died. The researchers said there was no evidence of super-spreader events in health-care facilities, like those that occurred during both the SARS and MERS outbreaks.

A super-spreader is a highly infectious patient who transmits the illness to many people at a disproportionately high rate. It is not known if differences in the virus itself or better prevention, or both, contributed to the lack of super-spreading of COVID-19, the researchers said.

Jimmy Whitworth, a professor of international public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said the study confirms previous impressions of COVID-19 as being relatively mild for most people.

"As seen in China, this virus can spread rapidly in populations, and can cause a major strain on health services simply by the sheer number of cases," Whitworth said in a commentary.

He said health services in other countries need to stay vigilant to identify all cases and to prevent further transmission.

The study's authors acknowledged the limitations of the study, including the fact that more than a third of cases had not been confirmed by nucleic acid tests because, while accurate, the process is slow and labour intensive.

No comments :

Post a Comment