A tiger in New York has tested positive for the coronavirus. The four-year-old Malayan tiger, called Nadia, is thought to have been infected by an asymptomatic keeper at Bronx Zoo. Authorities at the zoo became concerned when Nadia developed the coronavirus’ tell-tale dry cough.

Nadia is not the first animal to “catch” the infection. A dog in Hong Kong tested “weak positive” for the coronavirus in March, however, experts were confident the Pomeranian could not spread the virus to humans.

Six other big cats at the zoo, including lions, have also caught the infection and are all expected to make a full recovery. Early research suggests the coronavirus is mild in four out of five human cases, however, it can trigger a respiratory disease called COVID-19.

With more than 1.2 million human incidences being confirmed worldwide and the death toll exceeding 69,500, many are worried what animal infections may mean to the coronavirus pandemic.

The coronavirus is thought to have emerged at a seafood and live animal market in the Chinese city Wuhan, capital of Hubei province, at the end of last year.

It has since spread into more than 180 countries across every inhabited continent.

Since the outbreak was identified, more than 1.2 million cases have been confirmed, of whom over 264,400 have “recovered”, according to Johns Hopkins University.

Incidences have been plateauing in China since the end of February, and the US and Europe are now the worst-hit areas.

The UK has had more than 48,400 confirmed cases and over 4,900 deaths.

Can animals pass the coronavirus to humans?

While news of infected animals may sound alarming, the World Health Organization stresses “there is no evidence a dog, cat or any pet can transmit COVID-19”.

The circulating coronavirus is a new strain of a class of viruses, of which seven are known to infect humans.

Other strains include severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars), which killed 774 people during its 2002/3 outbreak.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (Mers) is also a coronavirus strain, which resulted in 858 fatalities during its 2012 outbreak.

Although unclear, both Sars and Mers are thought to have originated in bats.

Sars likely “jumped” into humans via the “intermediate host” palm masked civet, while Mers is thought to have gone from bats to camels to people.

Early research suggests the new coronavirus is 96% “identical” to a strain that infects bats.

Virtually unheard of at the start of the year, research into the new coronavirus is ongoing, with studies suggesting it may have jumped into humans via pangolins.

Based on what we know about coronaviruses as a class, it is widely accepted certain animals can pass the infection to humans.

The risk among pets – and zoo animals – however, is thought to be low.

There are two known strains of feline-specific coronaviruses.

“[The feline coronavirus] is genetically very different to [the circulating strain in humans],” said Professor Gilles Guillemin from Macquarie University in Sydney.

“This means that as long as the correct test was run on feline, it should be easy to differentiate between the two types of viruses.

“Previous studies of Sars showed cats can be infected and pass it on to other cats.

“But there was no indication during the Sars pandemic that Sars became widespread in house cats or was transmitted from cats to humans”.

The “weak positive” Pomeranian belonged to a 60-year-old woman with confirmed coronavirus.

“We have to differentiate between real infection and just detecting the presence of the virus,” Professor Jonathan Ball from the University of Nottingham said at the time.

“I think it’s questionable how relevant [the dog case] is to the human outbreak as most of the global outbreak has been driven by human-to-human transmission.

“I doubt it could spread to another dog or a human because of the low levels of the virus”.

Warning against “mass hysteria”, he added: “The fact the test result was weakly positive would suggest this is environmental contamination or simply the presence of coronavirus shed from human contact that has ended up in the dog’s samples”.

According to Professor Guillemin, thousands of tests had been carried out on pet dogs and cats in the US as of March, which all came back negative.

Professor Glenn Browning from The University of Melbourne added: “While there is some evidence cats can be infected, they do not appear to transmit the virus efficiently to other cats.

“On the limited information available, dogs appear to be resistant to infection.

“People appear to pose more risk to their pets than they do to us.”

Animals can become seriously unwell with coronavirus infections, like humans, according to Professor Guillemin.

Coronavirus: Should people avoid contact with animals?

While infected pets are not thought to pass the coronavirus to their owners, there is still much we do not know about this somewhat mysterious strain.

Britons who develop the tell-tale fever or cough have been told to self-isolate entirely at home for seven days, while other members of their household must do the same for two weeks.

During this time, government guidance urges suspected patients to avoid contact with pets, if possible.

“If we are going to stop this pandemic we need to take social distancing seriously, that includes all household members, humans and pets,” said Professor Jacqui Norris from The University of Sydney.

“Despite the absence of any evidence to support the transmission from animals to humans, it’s a smart measure to isolate your whole family.

“If a member of the household becomes sick with COVID-19, they should be isolated from all members of the household, pets included.”

Not all experts are convinced, however, pets pose a risk.

“At present there is still only one suspect case where an owner has spread the virus to their pet”, said Dr Sarah Caddy from the University of Cambridge.

“It is possible tigers in captivity are more susceptible to the virus than household moggies as there is a 5% difference between their genomes.

“The bottom line is that there is no evidence any cat, large or small, can transmit virus back to humans”.

That is not to say it will not one day be a risk, however.

The coronavirus is an RNA virus, which mutate almost constantly. In simple terms, RNA is a precursor to DNA.

When asked if the strain could mutate in animals and cause a second outbreak, Professor Guillemin said: “Coronaviruses have a high rate of mutation so this is still a possibility.”

It is unclear how significant a risk this may be.

What is the coronavirus?

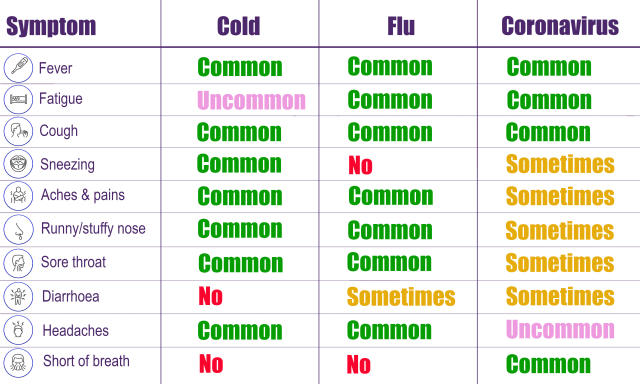

The coronavirus tends to cause flu-like symptoms, including fever, cough and slight breathlessness.

It mainly spreads face-to-face via infected droplets expelled in a cough or sneeze.

There is also evidence it may be transmitted in faeces and can survive on surfaces.

In severe cases, pneumonia can come about if the infection spreads to the air sacs in the lungs.

This causes them to become inflamed and filled with fluid or pus.

The lungs then struggle to draw in air, resulting in reduced oxygen in the bloodstream and a build-up of carbon dioxide.

The coronavirus has no “set” treatment, with most patients naturally fighting off the infection.

Those requiring hospitalisation are offered “supportive care”, like ventilation, while their immune system gets to work.

Officials urge people ward off the coronavirus by washing their hands regularly and maintaining social distancing.

No comments :

Post a Comment